TuneDig is an in-depth and informed conversation between two lifelong friends about the power of music — one album at a time.

In each episode, we go down the rabbit hole to spend a while in the strange world we discover. We take an honest look at creativity in all its complexity—from writing and production to history and cultural impact.

We promise you’ll learn something new every time, no matter how much you already love the album we explore.

DIG IT.

Subscribe by email to get new episode announcements and very occasional updates from TuneDig. ✌️

You can unsubscribe at any time. We won't sell your email address because we're not terrible people.

THE LATEST

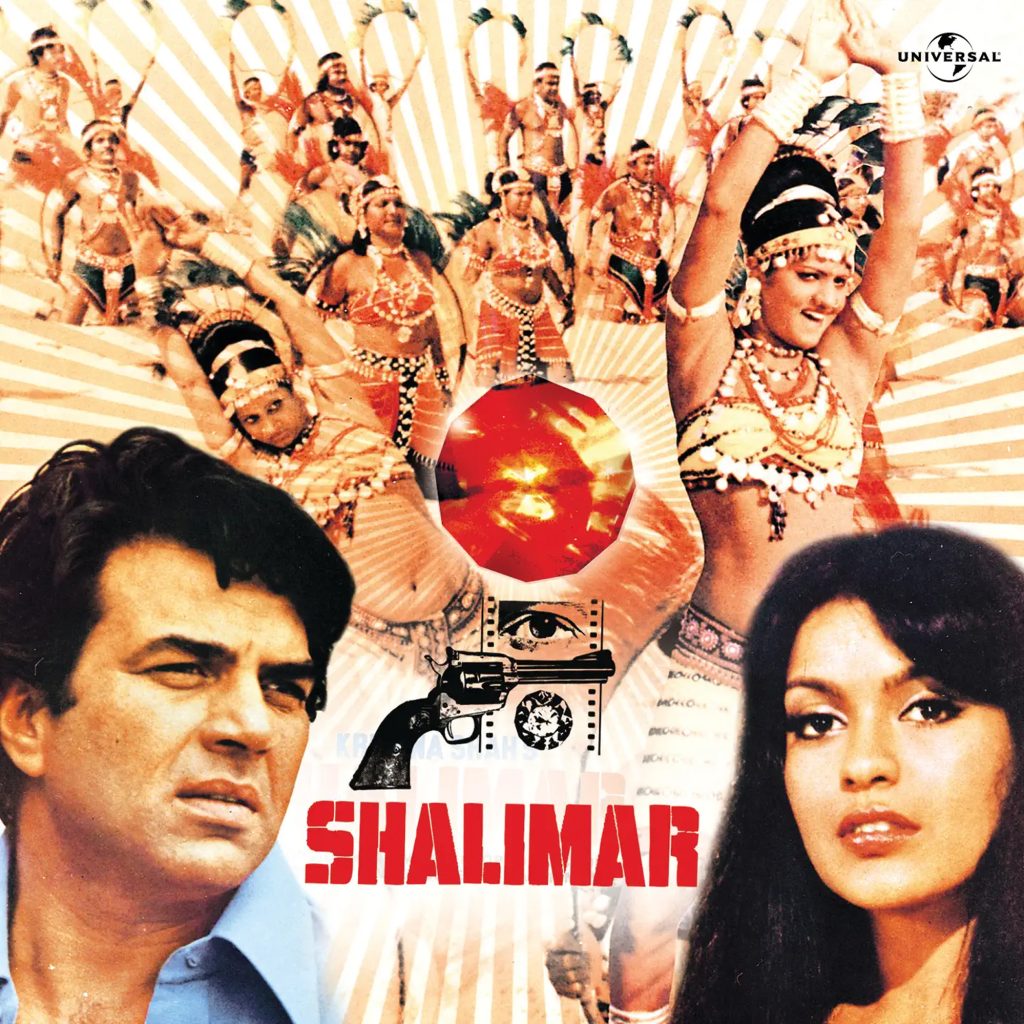

Episode 72

Shalimar

R.D. Burman

Once upon a time in Bollywood, one magical man made enough music to fill a million moments—and made space for hundreds of other artists along the way. Of the 331 scores “Pancham” composed in his lifetime, 1978’s “Shalimar” is a uniquely compelling introduction to his technical prowess, transcendent alchemy of cultures, and tremendously joyful love of a life full of song.

Transcript

Note: our transcripts are mostly AI-generated for now.

Kyle: Today we’re talking about the original soundtrack to Shalimar by Rahul Dev Berman.

Cliff: A soundtrack again

Kyle: Is this our third one?

Cliff: I’m not sure what the third one is you’re thinking of.

Kyle: Fantastic Planet.

Cliff: Oh

Kyle: good, bad, and ugly. And

Cliff: Yeah.

Kyle: now this one,

Cliff: Fantastic. Planet was so far beyond feeling like it belonged to a movie that I keep forgetting.

Kyle: it was like, yeah. Made an album and had to invent blue aliens to make it make sense.

Cliff: yeah. But also, as opposed to, I would say either of the other soundtracks we have or will now talk about, fantastic Planet Feels. there’s too much hip hop in me to start with that I could never hear that record as a sort of original objective thing that existed because we’ve heard too much of it already in other things.

Kyle: totally fair.

Cliff: whereas for sure, good bad in the ugly started to split all from that. And then this one for the most part entirely. Not like that.

Kyle: Yeah. Although right away dropping in on it, I was like, this has been sampled. Surely there were so many moments that I’m like, this has been sampled a ton and it just hasn’t, and it really surprised me about. His life and legacy. And until I learned that, that feels like maybe par for the course in terms of global appreciation.

But I mean, we’re talking about a guy that was talked about by his collaborators as in the top three composers globally of the 20th century. Am I getting that right?

Cliff: Oh yeah, they said that with a straight face

Kyle: behind Pacini of Madam Butterfly fame, Richard Rogers,

who did tons of American musicals,

Cliff: Sound of music.

Kyle: sound of music among them, lauded the three of them in a through line for writing quote standards, known the world over. and while I could ignorantly say that’s objectively not true, ’cause I had never heard a lick. Of this man’s music until we started digging in. Like I had a passing interest when we put it on the calendar. saw that it was a Bollywood soundtrack on the thousand one albums. You must hear before you die. Listen through. It was like, yep, this is tight. Let’s do it. Didn’t really give it much more thought. but sometimes your instincts can reveal something deeper later. and I think what it revealed for me, like I just keep thinking about the Prince benediction of dearly beloved we’re gathered here today to, he says, get through this thing called life, but to celebrate this thing called life like starting off 2026, trying to, everybody’s trying to shake the weight of last year. ‘Cause you. Time isn’t a real thing, but we use this opportunity to make it one, and that’s good and fine, but like we need, uh, we need a bellwether, we need something to hold on to. And there’s just so much in this dude’s life that’s like an explosion of flowers and color and beauty and he just had so much extra to give and other people received it.

So bountifully and warmly, that I’m on the Rd Berman train and I hope we can get others on the Rd Berman train accordingly. Like I, I think we both, I’m taking our exchange of messages the right way, we’re a little bit like, yeah, okay, this will be cool to do. Like, let’s talk Bollywood, let’s continue expanding on the, holy shit.

There’s so much going on in the Indian music and. Arts ecosystem. we’ll never even scratch the surface, but let’s keep trying, scratch the itch that Ravi started. But it wasn’t singularly like about the artist. And I think we both slowly had this realization, like, okay, well, alright, hold on, hold on.

I gotta take this real seriously. Now

Cliff: Slowly and then all at once

Kyle: that’s right.

Cliff: this one was on, ironically, a great example of like, I want to talk more about what you just said and specifically how this got picked on a calendar. Then how we still have this experience despite knowing that it was already worth listening to and having a passing enough familiarity to say we should listen to this once a year and other people should too.

And like I also think that the laundering in of this particular soundtrack through 1,001 albums is itself a really interesting way to get anyone listening like 50% of the way into this thing very, very quickly. ’cause I think just explaining how it surprised us and then what changed our minds really quickly is gonna give a better lead in than just trying to hit facts about this.

’cause it’s full of interesting trivia, for lack of a better word, about the recording and composition process. But that had a lightness to it until I understood more about Rd Berman specifically and his path and the stories and the way that he impacted people.

Kyle: Yeah. Do you,

do you wanna start with what surprised you with the music? Or do you wanna start with his path? Because I think both places are interesting to jump in.

Cliff: a fun third option that’ll take me to both, so.

Kyle: Neither. Bitch. I want to talk about the dollar menu at Wendy’s.

Cliff: Well, yeah. I mean, they make Wendy Cindys now they’re single pieces of chicken. They’re delicious. So the 1001 albums thing, I myself have an interesting sort of relationship to it, and I think this podcast does too, in that we’re sort of doing really similar things, in terms of just shut up and go listen to music.

shut

up, shut up. Go

listen to music until you’re tired

of it, and then go tell me what I did

wrong. Because as soon as you start telling me what I did wrong on my list of things you should

listen to, you’re doing the thing I

wanted you to do. Voila. a whole trick. That’s our entire rug pull is to just get you being cooler by listening to cooler fucking music all

the time.

’cause it works and it makes you a more interesting person.

Kyle: It is a very neggy way to, that that is probably kind of where, why are you hitting yourself? Why are you hitting her? Like, stop listening to Radiohead all the

time. Listen to

some other shit

instead.

Cliff: so it probably has that tone because the main thing I

noticed that made me wanna talk about this

was, so there’s like a website that then collects all the 1001 albums and,

Reflects them back to you. Now, I don’t know who made

this website, but they made the cardinal internet mistake, which is that they opened up comments on anything.

So all of those albums just have a comment section, the way that. things on the internet used to before we understood how people really are on The inside and how they talk to each other.

Kyle: the worst.

Cliff: yeah, and just like, oh no, we don’t need to see this actually.

Kyle: Yeah. Shut up. Shut up. Shut up.

Cliff: yeah. So then to that end on this one, on the Shallow Lamar soundtrack on 1001 albums, there are what I feel are fair, but, pretty negative comments about, Hey dude, you have like 200 British indie pop albums comprising 20% of this entire list, and you got one fucking album from India and it’s a soundtrack to a half shitty movie. What are you doing? And like, do you think you could consider a better introduction to an entire giant fucking country? And an entire tradition of music that’s deep and incredible and all that.

Kyle: Wait, the, it’s the only Indian entry on the whole list, or it’s just like one of a

Cliff: so I wanna be clear, according to the comment section Yes. at, at a tertiary glance. I see what they’re saying. I think that that’s probably more or less true.

Kyle: There is so much bullshit on that list. I mean,

Cliff: I can appreciate that it exists. We would also never, ever pick those 1001 albums for a million defensible reasons. So

Kyle: I do appreciate that there is like kind of a Strava culture around the thousand one albums list that it has generated momentum. Just by existing, good or bad to, I agree with you about the like, well, I told you that you’re bow-legged, but now you’re running or whatever type thing.

That’s, that’s like a not nice thing to say, but, however, we got here, we’re here now. Uh, and you’re listening to something and thinking and talking about it and using it to interact with other human beings. but I do really, I am really fascinated by it, and I see a lot of it on TikTok, the people that decide as a New Year’s resolution to go on a mind expansion journey in the spirit of the calendar and earnestly, like they’re the first person to ever think of it.

And I mean this lovingly, they will like dutifully listen to the album and just say their immediate reaction thoughts about the album. And like, hundreds, if not thousands of new people do it every year. And it fascinates me. again, it is the same sort of headspace of why we did the

calendar, but we did it in a certain way, in a sequence for maximum diversity of

sound.

That’s definitely a differentiator from the thousand one things. And did it mostly for

ourselves and not for, the little Reddit

on the one little web 1.0 site 1,001

albums.

Cliff: So yes to

all that? we are cruising on the same line together ’cause that’s 0.1 is overall

in theory, we’re probably talking about this album right now because it was on 1001

albums. And

that is interesting and I like that it, happened that way for two reasons. One will pay off for everybody

else and one pays off for me right now. That

triggered a real moment in me when I saw those comments

and I went, wait a minute, why do

we have this on the calendar and why are we about to talk about it?

I

want to make sure that we are doing something different than what people are responding to on this page. This thought of like, Hey dude, if you’re going to put your toe into the entire world of Indian music, do something respectful about it.

Okay? So. It triggered a little defensiveness in me, which quickly closed the loop though. So a couple of things. One, this is not the best introduction to the country of India, or its music, or its history or any of that. It should not be that we’re not talking about it from that perspective.

Kyle: Or perhaps Rd Berman himself.

Cliff: Exactly, yes. if you want a more appropriately, and I mean this with a stray face, like in a more appropriately reverent introduction to any of this, we have a Ravi Shankar episode. just do

that, that. From there we were

able to

Kyle: Fully acknowledging though that that’s like,

hi, you wanna talk about Western music? Here’s one Beatles album. You know,

like it’s the biggest sort of broadest

introduction possible. It’s not, you know, we’re not going to the John, well, maybe we are kind of going to the John Coltrane. Like he was a lot of things to, to Indian music.

It’s, it, there’s not a direct analog, but

full fully acknowledging it’s a great entry point because it is so broad and also so technically proficient. But I think a lot of

people. Indian people especially would be like, okay, maybe not necessarily something so

stereotypically that, but it’s okay.

’cause you got, you gotta start somewhere. As long as you’re acknowledging with like a humility, like I don’t know shit about shit except that there’s so much to the Indian subcontinent and the tapestry of human experience in general. And man, I just have to start like I just gotta put one foot in front of the other.

Cliff: Exactly.

Kyle: So I hope anyone listening to this is feeling a little bit of that swirl as we’re talking about, like, this is not a good entry point. Like, oh no, but what is, don’t worry about it. We’re here now we’re gonna do it.

This is fun. Let’s just keep going.

Cliff: yep. There is no pure right answer,

Kyle: And the longer we do this, the more we realize like that’s, it’s all just kind of for your own purpose anyway. Trying to come up with that.

Cliff: Yes. fully agreed with everything. I would just also add though, if you were interested specifically in some of the musicality of what came from Indian music. The Robbie Shakar episode

will have more, especially from me about those details than we will see here specifically because, and here, here is where we can make a really great turn, specifically because Rd Berman did

the, thing that we love about artists where he introduced unexpected irreverent concepts

into his music, both through a mixture of

creative energy and through, you know it seems over the years he would also be pressured to integrate certain aspects of Western

music. So there are different aspects

of borrowing and transposing and co-opting and everything, but we are often

really talking about it, from western perspectives and from hip hop samples and blues and all that. And we’ll get to probably make those analogies. But this is like a unique

way of viewing

another like full scope of music that we usually don’t have a lot of access to.

And by that I mean just the

prolific amount of soundtrack and composition music that

Artie Berman did and how, why the fuck did

Cliff talk about all this to start with? Because going through that

problem of, wait, why am I listening to

this right now? Turned a corner for me into not only, oh, this is why,

but like I had.

A much more open spirit about the music that was here in a way that

changed me in a

really cheesy

way. and

I kind of hate having these experiences with

albums and we keep talking about them together, but like, I just can’t stop being a little

more tender every time I learn something about someone who really cared about

their music.

and it always

changes me a little bit more to then go back and listen to that music again once I know a

little bit more about them and like, I

just, I don’t know, There’s not too much. That’s better to me.

Kyle: I, agree. People talked about how he

was. One of the quotes I think was overflowing with all kinds of music. Like it was literally going, I had so

many, he’s just like, me for real moments. Like he, he did a lot more about it. He was constantly making things, he was

like consumed by it, but it came out of him, it was contained in him and came out of

him in a really joyous way.

And I was trying to think of other people who exist right

now that I’m really inspired by. I kept thinking of the phrase that’s the title of that Charlie XCX song. Everything is romantic. Like he found a

beauty and I’m excited for us to get into a couple of dimensions of the music that make me feel this way.

But he like found a beauty and I think Bollywood, from the very little exposure to Bollywood cinema that I have really focuses on romanticism about.

A lot of different elements of like actual romance, but the adventure of life and just of a good story. And that

sort of like the romanticism, the romantic sizing is way over the top and that’s some of what makes Bollywood kitschy, but it’s what makes it enduring and beautiful.

I also thought about, to your point, why 19 70, 78 shallow Mar when he did 331 scores? Does that sound right?

North of three. Oh, north of 300.

I thought about there’s a romance to just plowing through your letterbox queue and it’s like, it’s Tuesday. I got nothing. Let me pick this.

Sea grade thing that I don’t even know how it got on this list. And then it winds up being like a thing that you really love and you tell everybody about for six months. And I think about how Raygun from Chat Pile, who we just saw together in person at the Decibel Fest, given big shout outs, to that Vinegar Syndrome store in Denver, and then doing a 12 hour movie marathon the next day after a big performance.

and then I also thought about I wanna hate the guy. I feel like we’ve maybe talked about him on the pod before, but Timothy Chalamet, like Marty Supreme stuff is kind of everywhere, has been kind of everywhere the past handful of weeks. And his passion, his ability to speak to film and the language of film, but also to like go on inside the NBA. Or make picks on college game day and talk stats at a really nerdy level. that shit, whatever that ethos is on how to be alive, that’s Tune Dig. That’s why this thing has sustained for such a long time. And you and I have been friends for such a long time ’cause it’s like, we’re like Lucille Ball and the and Ethel Merman in the, bakery assembly line scene.

Like we just have two min, like the little pastries are just the new things we found that we’ve love, we love or old things that we rediscover and we’re just fucking shoving them into the corners of our mouths and like feeding

each other and whatever. And when life sucks, like that’s the only way I know how to hard

reset is to

find people that just like have the factory moving at full steam. And he did. Shalimar is a random entry. It’s like a. It’s maybe a little bit of a deformed pastry on the line. Humans explode in it. So that may or that may or may not be your thing. There is a non-zero amount of human explosion,

Cliff: Oh, I watched the movie. I would go ahead and

Kyle: presented to audiences as like a Indiana Jones type romp, but it’s, it’s fucking farcical at some points. there was another thing in that documentary where people were like, I’ve rewatched this movie 50 times. Not ’cause it’s a good movie, but because the music bangs, like multiple people said something to that effect.

Cliff: a little fun anecdote specifically about this movie and soundtrack was that the one two cha cha cha was so big with college aged kids in India that apparently they were going to the movie only for this song and then leaving like a. DIY music video experience,

I guess, which is cool.

Kyle: Or sort of like the people that go to throw popcorn at the chicken jockey scene or whatever. A bit of that.

Cliff: The story sounded a bit like bullshit, but the fact that the story existed at all sounded fun and interesting. And then, but every little bit here, and I know we’ll start talking about them in specifics now, but like, there are so many little, like, oh, that’s fun. Oh, interesting. Oh, weird. Oh, oh, okay. Oh, he did?

Oh, so that was on purpose. Oh, okay. That’s cheesy and weird. Okay. But that’s cool. Underneath it. And just you kind of can’t ever sit with anything here, including the movie as something we’re totally writing off, because, you know, the soundtrack itself makes the movie fascinating in ways that I’ll go ahead and say, I don’t think you need to watch this movie necessarily to squeeze most of the juice out of this soundtrack, but especially once you start appreciating it, it makes watching the movie itself interesting to then see how, Some of it yes. Is just make a movie soundtrack for a Bollywood movie. That sounds a bit like Western stuff. Yes. Sometimes that happens, but a lot of times the way that any of that stuff happens is clever, deceptively clever in a way that doesn’t really belong. And that’s what’s made me love this dude as a composer now.

Kyle: totally agree. And although I will also say, I think of the three scores that we’ve done, this is the most listenable, completely out of context of the film. Goraguer’s Fantastic Planet score, also great, you know, propelled to even more greatness by like the hip hop reuse. but I think this is just an interesting slab of music, even if no one ever told you it was for a film

Cliff: Yep.

Kyle: With all respect to Ennio and all the tremendously influential spaghetti western stuff that he did.

Cliff: Yeah. But this one’s like. If that woo, that if that sound was happening as a hook 37 times throughout the rest of the album and not just repeating it, but actually like, no, I have 37 original hooks like that. that’s what this one’s, like, you start listening to this you’re just like Jay-Z GIF-ing all day.

You’re just starting to bop at shit you don’t think makes any sense. Like we will either do a track by track or come very close to it here soon because like there are just like a bunch of places that I just wrote down, like, oh shit, like 41 seconds into this one. Oh shit, two minutes in.

Oh shit. But

Kyle: Well, let’s do that. Let, let’s jump there. I want your list with as many of those footnotes as possible. I did make a footnote specifically with one two Cha cha cha. My first thought was, cliff is going to hate this. oh, oh no. What I wrote was, oh, we’re definitely gonna lose Cliff.

Cliff: I, I’ve learned to love it actually, let’s just start there. I don’t need to go in order because nothing here really feels like a

chronological anyway, so let’s just start with that one. Especially ’cause it’s more or less than the most known song here to begin with. So yeah, there is, a layer for me as a Western listener, a layer of cheese that I was uncomfortable with for multiple listens, And then two things helped me out and one of them was more fun musically, and one of them is just, oh, I like this energy now and I understood it. So one is just at around two minutes this song does a total like dropout and then builds back outta nowhere. And like objectively it’s sick.

It is a musical move that doesn’t feel like it belongs anywhere near any of this. And once I let myself go, oh, he does moves. That unlocked a lot of stuff for me because we, you and I, Kyle will talk about musicians who do moves and we sort of mean it different than just he does a riff or there’s a noticeable production technique or, so it’s like

you can,

Kyle: Stu Stunty A little but not, I can call it a stunt and it’s not weird or stupid ’cause it works. they finesse it. it is like a fan. It’s like an and one highlight type thing. Like it, watch

Cliff: So I was about to say, as long as we agree that it’s a stunt in that it’s also kind of stunting on them. Yes. Like that is, you get the feeling through the music that someone in a studio went, yeah. Fuck yeah,

dude Yeah. Yeah. for

Kyle: Uh, but I agree that that’s more it, it’s not Prince “singular genius” where he’d be like, watch this. It’s like his collaborators all talked about his generosity of spirit and how he’d listened to ideas. And if he liked the input, then he would use it and he would always credit the person and such a breath of fresh air after all this fuck ass bad behavior we’ve had to talk about, seems like there’s a general consistent year over year data point of he wasn’t perfect, but

like, he was really great to work with.

he specifically

worked with singers and had a feedback like.

I want to go show it to people at work to talk about leadership. Like he used positive reinforcement and instead of being

like, that sucked, you should do a different thing. Like, you’re fantastic. You’re so good, but we really need

to get this part a little more in key to

take the whole thing to the next level.

And I know you’re capable of it. unbelievable. And he did it consistently. It was like Mr. Rogers. He never deviated from

that vibe. I couldn’t find any stories

that, he did. and it it just worked consistently for him. so that kind of

blew me away.

Cliff: Totally. I’m glad

you mentioned that, that I’m going to remember that part of Poncho Man mix the documentary for a while. Like that was where I started

listening in differently because for someone, so again, two things are always

happening at once. Somehow, every time I find something interesting here, one of them is You hear the singer describe herself, the experience you just talked about, right. So it’s not, it’s not someone else

saying in general, this is how I remember

him working.

Kyle: Not, not like a long time engineer

type person.

Cliff: And

so you get to cut

through that thing that happens, especially when great musicians and composers die, where it’s like, we’re going to crystallize them exactly the way we wanna talk about them forever.

So we’ll just talk about the way

that they were in a sort of general sense. Maybe it’s accurate, maybe not. But here

we heard from a person who was performing something specific. And the more you can

learn about Rd Berman, the more you’ll

see, like you mentioned Kyle, he was constantly working

things and collaborating with people.

So a singer

is performing. another part of this same documentary, like the, the vocalists would talk about like, we are

performing what Ponto says, what we are doing, what Rd Berman told

us to do. In, in that sense, I, as a vocalist feel

more like I’m representing him than myself.

Kyle: Yeah, somebody was, somebody was like, I’m just a

robot that does what he says to do, or something.

Cliff: so in that sense, we know that

Rd Berman is

working things. Often and trying to get people on board with

what’s in his brain. so the two things that happened when I heard that, so one is the

Just that energy of creativity and

the me and you, Kyle, specifically love this particular form of pushing people to be

creative.

this is the way in all capital

fucking letters. It works better. You leave a more lasting impact on other people. the product is better,

all that. so there was just one on one hand optimism, like, I, I need to go further into this because there

is care in every note

that exists in a composition from this dude. And that’s how I know it,

The second thing that happened

simultaneously, which I’m sure you’ll appreciate and

laugh along with is this

is 20 25, 20 26. I am very

used to the sensation of, oh, I see a cool thing from a

man. Oh, oh, I better go figure out all the rest of the stuff that I need to know now so I can contextualize how I feel about

this.

And you know, we, we can’t know every detail of

everyone’s life, but like I was really pleased to

discover that when people talked about him at his time of death and beyond, they continued to express a person that they knew who acted this way the

entire time. And the worst critiques they had of Rd Berman and his personality was basically that he crashed out in the eighties and got super fucking sad about a lot of stuff. And that’s a pill that I can swallow when I’m trying to understand something more about a musician. Whereas,

Let’s make an easy pull.

Miles. Davis got a lot out of other

people and he was a huge dick about it. Now

does that mean we could have gotten something better out of a nicer Miles Davis from Cliff’s?

Personal argument, vantage point, yes, actually. But I understand that that doesn’t kind of matter

and that’s like a different person. But to be able to like lean into Artie Berman specifically and go like, I can care about this music because I know that he cared about the people who were making it and that he cared about every note in a way that’s different from just being a perfectionist has helped me connect emotionally with what is going on in this soundtrack.

Kyle: Yeah, you kind of can’t resist the joy and the optimism in it. And you talked about Miles Davis being abusive, like the obvious counterpoint for me the right now, topical counterpoint watching Poncho Unmixed was Diddy. Like having just watched the Diddy documentary and being like, well that’s one way to go about, thinking of people in the world and, maybe they’re not perfectly on other, on opposite ends of the spectrum from each other, but it was a great refresher for me.

You watch the Diddy documentary and you’re like, man, people are so, people are capable of being so fucked up. and then you watch this and you’re like, oh, the human spirit is indomitable. And together we can do anything and maybe I will stay alive for another year. You know, like maybe I, maybe I will keep doing the group project.

Instead of holing myself up on wooded property,

Cliff: Never kill yourself until you’ve cleared the entire discography of Berman.

Kyle: oh my god. “Don’t kill yourself. I’m gonna Clockwork Orange you with 6,000 hours of Bollywood films, and then if you still want to kill yourself afterwards, and we’ll talk about it.” There was also in one two Cha Chacha, I just rewatched Austin Powers as well. ’cause I was like, is it going to be a light fun watch or is it going to be problematic?

And the answer is the third thing. It’s both, But the first thing that I thought of when I heard one, two cha cha cha, it was like, oh, it’s the same thing. It’s sixties UK mod, goofiness, whatever. But then maybe we’re talking about the same thing in the song. It drops out pretty quickly into something that reminded me of Black Mo Super Rainbow.

it got kind of psychedelic. And that was another thing that I noticed in the first handful of listens was whatever the modality of the song is and like the mood that they were setting. There’s kind of a lot of jamming or almost psyching out in sort of a jazz way in sort of a textural score way. But it’s, it’s not really either of those things, you know?

And it’s not really like the Grateful Dead. it sort of does its own thing. It’s like, this is a good groove. Let’s just let it breathe. A little, they just let Seth breathe. and it’s not strictly narrative. You know, like one of my favorite score composers to listen to is Trent Resner Attic, Atticus Ross.

But it’s like, that’s straight ahead. It’s serving an airtight linear narrative scene and pushes accordingly. This does a different thing. And so there’s enough vibe and space in it where you could see like some of, these compositions being performed live, but it’s also not hugely expansive necessarily. Like Mingus, thinking about Mingus as a counterpoint, as a composer, you can see where that would go in long directions for a long period of time. I don’t know, man. I just, it is its own thing when you think about it sonically, but also from a composition slash maybe jamming perspective as well.

I’d be interested for your reflections on the jamminess.

Cliff: A hundred percent. I love how

much of it exists here to the point that it

became really endearing how he borrowed things in a

specific way And I think one of those reasons is that he

would frequently mix

rhythm This is even hard to express verbally, but like we have common concepts of rhythms and cadences and beats and whatever that are like cultural

to us.

I mean at

this point, like 8 0 8, some shit for an American are like a whole, like trap beats feel away, right? so in that sense there, there’s just a lot of familiar rhythmic moves

that come out culturally, and for the most part, those are very hard to overlap or interconnect. Usually what we see in hip hop for

instance, is the rhythm of one thing and the melody of another thing, and then maybe layers of other things on top of that,

right?

we sort of make that sandwich. What Artie Berman does almost constantly is intermixing

rhythmic cadences from different cultures. And so one, two cha cha cha is, I mean, from an overly academic

standpoint, this film

is, in Hindi and

English, so there is Hindustani

cadence in what’s happening in this song.

And then it over overlaps with, now we just think of it as chacha, but like these are Latin rhythms and those were not necessarily designed to be mixed together at any point, and certainly not this early

on. So to have that is what creates the moments that me and you are talking about, where, like,

inside of this otherwise fairly

cheesy song, there are noticeable transitions between movements of a song

that’s otherwise pretty much a short pop song.

so again, the more you look, the more you start to

see the complexity and the layering that’s gone into it a bit. And

to that extent, like you know, this is a really easy call for me to make here. But like you mentioned,

the kind of jamming influence that’s here. One easy one to call out immediately here

on this track is that,

is what the Mars Volta does that I

love.

They are, they often

take especially Latin rhythm and percussion and then they integrate

psychedelics, they, you know, and then later on, you know,

other more kind of electronica based concepts and cadences and all that. But they’re often putting a Cuban, a Latin, something into a

rhythm to complicate it.

And then they layer, like now it’s just melody or

psych or whatever, sort of on top of that. And this is the most head screwed on version

of what the Mars Volta does. This always keeps its wits, every song, every moment of rhythm intermixing or shifting or changing

you as a. You, me, us idiots, we can

follow it every time.

Like it, it doesn’t, it never shocks you in a way that confuses

you, which is a fun

aspect of this. So much when you see, or, or so often when you see complexity, especially

rhythmic complexity, especially to the degree that you’ll see that Rd Berman was working with. When you watch this documentary, like this level of complexity usually scares people off to your Mingus point. It becomes overwhelming

and difficult to track, and like that never happens

here, and that’s, so cool. It’s

almost annoying.

Kyle: I totally agree with that. There’s also a bit in the book. about this thing called the Pancham beat, which you mentioned, hip hop, interpolation and blues and whatever. I, I thought of the Bo Didley beat and you talking about

like the Mars Volta “Mars Volta-fying” the rhythm, so you always know it’s them. I’ve never really thought of their music that way in the countless hours we’ve listened to them and talked to them, but that’s totally true. there was a bit in the book about how composers before him had

started to popularize or sporadically used and maybe inspired

other people in the, what was described as fraternity of

composers. Like things like the

fox trot, the

polka, like pulling in things that are western and weird.

And, I like the way you put it. It’s just Like it, Makes it feel foreign and different, on, on purpose. There was this

thing about the poncho beat though, or the trap key beat that they called it, but people referred to it as the poncho

beat, playing notes with the palm rather than the fingers.

And it was a sound that he fashioned by inserting a thin metal foil between, the instrument and the body, the belt that runs laterally across the length of it. in the book they also said, the genesis of the beat was one morning, a household

help was rubbing a piece of newspaper against the floor with

her foot to remove stains, and the act of rubbing at a particular place resulted in a different kind of sound,

which aroused poncho’s interest. He summoned the help to continue gener generating

the sound, which he recreated in the studio by rubbing a

piece of aluminum foil on a coal, a tribal leather instrument used widely in mingle.

which Estee his father

specifically procured for the song, he had this cool thing making

me think about like, blog artists and weirdos, like black mos, super rainbow again with found sounds and,

making a beat out of anything. and we talked about that in the Tom Waits episode, like New

York was a character musically that found sounds, came outta that. And there’s an interesting foil with his father

who was also compo, like there’s a whole rabbit hole there.

His father was a composer composed for over a hundred films.

Cliff: And his mother was a lyricist,

Kyle: his

Cliff: into it, man.

Yeah.

Kyle: born into royalty in more ways than

one.

His dad was a prince from a royal family. so there’s definitely a like

strokes, Wikipedia, blue hyperlink parent thing going on here, but

he definitely found his own path. and there’s probably we that we could spend a lot of time talking about that phenomenon and unpacking how we respectively feel about it.

But anyway, his father was sort of famously a minimalist in his compositions. rd on the other hand, was, a pioneer of using large and diverse orchestras and like kind of a wall of sound thing. So in addition to the. Amount of experimentation that he was doing and being willing to sort of pull in anything from anywhere.

he did put a lot of things in recordings, so you’ll hear things to your point, weave in and out just within tracks, just within little movements. So there’s lots of little stuff that you kind of gotta be listening on good speakers to catch, but you hear some of that in one, two cha cha cha.

But where I think you hear a lot of that is in the, title song. the first track on the album for sure. We’re like, I listened to it with AirPods and it was kind of loud where I was, and I was like, all right, this is cool. And then I listened on really big, good speakers and was like, holy shit, there is a lot going on here. So I think you need that immersion moment also to, to take it seriously.

Having said all of that, tell me about some other moments, some other tracks or, things that surprised you or jumped out at

you.

Cliff: Will do. But on plus wanting that phenomenon, this one probably more

than any record I’ve listened to in recent memory, sounds fully asked different on

different speakers, headphones, every time.

Kyle: cra it’s like layers get fully hidden. Yeah, I,

it, it’s almost shocking. It’s very, very

jarring.

need, I need an audiologist to point

out what’s happening there and if, if I’m the problem

Cliff: I was just about to make fun of us. Like loving music is just going in a constant cycle of buying nicer ways to listen to music and then going, I didn’t need to do that. but for this one,

it’s like I, I legitimately can hear something different with good open back headphones and a headphone amplifier.

Like I can, reach into that room and get a little room

sound for myself if I listen to it.

Right. And this is wild. So a bunch of these moments for sure, just kind of like me going, okay. Speaking of title music, very first track, about a Minute

In is the first beat that hits me that now I love that I didn’t

really catch onto the first time, but 40, 45 seconds later.

So by a minute and 45 into this thing, this could have been a Can song.

I am fascinated by how obvious some of the transitions are and then how unnoticeable

some of them become. And you just find yourself listening to craw rock

somehow in a few times throughout this record or throughout the soundtrack in the same way that you just find

yourself listening to jazz.

And like

some of that jazz is old and then some of that jazz I’m gonna come back to this later on a specific song. Some of this jazz feels like it could be, it was Made Today by a TikTok family full of people sitting in a living

room like, doing that vibe now where it’s like, check out how fucking cool we are all together.

And it’s like, it sounds exactly like that. So

lots of this stuff threw out. so title music again, transitions pretty quickly to me from a cool beat into

something psychedelic. We at one two cha cha cha, we had dialogue then

after that, which, it reminds you

you’re listening to a soundtrack and actually starts with a little mixture of the movie and stuff.

But once again, by a minute and five into

this thing, you’ve got what I can only describe as a half musical,

half psychedelic thing happening at this. This feels cheesy, but wait, it isn’t.

That’s cool. Wait, I don’t know how I feel about this. And then on top of it,

as this song goes along, they break out

some like group chant noises that

activate not only

the part of me that now loves fellow coie in a totally different

way than I ever did in my life before,

Kyle: Which

track are we talking about?

Cliff: dialogue.

Kyle: Oh, yeah, yeah, yeah. But also,

god, white guy pronunciation incoming: Hum Bewafa Hargiz Na Thay, which translates roughly to, I

wasn’t dishonest, But I wasn’t able to be honest, which provides some intrigue into the film bit. yeah. All right.

Cliff: but in this one, everyone’s gonna hate me for this, but I’m fucking doing it all on this one. It’s the one that’s like, Ooh, ooh. what?

What? I don’t know how, as somebody who cares about

music, I could listen to this a few times through and

not think that was the coolest fucking thing I’d heard in a while. But now I can’t unhear it as that. And once

again, it’s just like, man, it’s got me, it’s got me wanting to do like gang vocals at a hardcore show. Why do I wanna participate in this Hindi soundtrack from 1978?

Like the amount that this soundtrack

managed to break down the walls of like what I insist is cool,

is unparalleled.

this is like a Rosetta Stone to get me to break down all of my social anxieties about who I’m supposed to be. I don’t know why.

Kyle: I love that, and I think that’s a good opportunity for reflection, just thinking about how differently people can think about. The same thing. You know, you’re talking about wanting to really engage with songs on a soundtrack like they’re pop songs or like they’re classic oldies melodies or, so they’re just something that are like ingrained in you.

And when you listen to people talk about RD Berman, they’re talking about he’s given us these songs that get stuck in your head and you can sing anywhere and whatever. And part of that is the singers he’s worked with and the great lyricists he’s worked with and all that. but then try to think of it with a western equivalent when you think about soundtracks with memorable songs.

And the biggest example I can think of is, Whitney Houston’s, I will Always Love You for The Bodyguard, or something like that. Or like even the Celine Dion song for Titanic. You know, like I immediately go to the nineties when huge song with huge movie. But they were always two very separate artifacts, even in the interesting case of The Bodyguard where it was, you know, Whitney Houston ostensibly her character projecting into this Dolly Parton song.

But that’s just like a whole different approach to these things are infused into the world of the movie, but not in a musical theater way. You know, they’re not in world necessarily in that way, but they help tell the story a little, or they evoke the feelings of the story and they’re catchy as fuck. And you, you find yourself walking away with like pieces of melody or interesting musical ideas from them.

There’s just a, like, I don’t have a good equivalent for. All the lifting that’s doing visually and aurally and it’s so interesting to me and it makes me wanna, like, makes me wanna stay with it. ’cause there’s just can’t find anything that feels like contains all of that kind of all in one place.

Cliff: Among the, 30 reasons, independent reasons will give you to listen to all of this music and more like what you’re pointing out, Kyle, you’re much more of a cinephile than I am admittedly, but I care about the music in movies and among the things that aren’t what they used to be, the level of craft and the, the like intrigue in what you’re pointing out.

The sort of like world meshing of the music thing that’s being created and then the movie that it goes on top of and sits within, like they make contact in this interesting artistic way. I don’t ever feel like that happens in movies anymore. the, the, at best I am pleasantly surprised by the choices in a movie, but they rarely strike you and integrate the things that are happening in it in interesting ways that also still make for interesting music anymore.

I really feel like, speaking of Trent Resner, like that was one of the last great instances of like truly visceral, soundtrack music that you could feel being a part of a thing that you were watching. And I really miss that. I feel like now we either get overly bland, like John Williams copy of a copy type shit.

I mean a copy of John Williams, I don’t mean that John Williams would copy people, but like a sort of like, oh, let’s make an orchestral sweep for this moment. Or on the other hand, and now I’ll lovingly talk a little bit of shit, but like, people like James Gunn are making cool movies now and they put what people think are cool songs in there and like, I wish I could teach the directors to have great taste in music because it’s, I can feel the energy of, I want the music to matter in this movie, but there are no Artie Bermans to be found.

I need these movie producers to find someone who’s like, I will be kind to you, but also you don’t know anything about anything, and I need you to give me time to fucking conjure this music from nothing so that it makes your art better. I don’t see that very much anymore, at least at the meeting of audio and visual mediums.

Kyle: I am on board with the passion and the shit talk, and I’m gonna be thinking for a while about whether I agree or disagree with the characterization. I think in broad strokes, the spirit of it, I. I agree with, and you know, that’s a whole other long conversation of like, the film and TV industry is just fucked.

So nothing is as good now as it as it was a little while ago. it’s fucked and has no ability to course correct for quite some time. I also think your James Gunpoint is a fantastic one because my initial instinct, was well, when people wanna do that, when they want to integrate music into the world and make it powerful, it’s a needle drop.

Now it’s not original music, right? And I’m like, oh, is that lazy? Do I hate that? Is everything trying to be guardians of the galaxy now? made me go to all while you were talking, by the way, uh, made me go to Robert Pattinson and, the Nirvana, something in the way. Drop and, you know, they, they sort of like stretched that out to its most fibrous and immediately TikTok was like something in my ass.

so like a needle drop can be a little too earnest or on the nose and maybe original would be better. The counterpoint that I would offer going back to Shaima is Marty Supreme and a, a number of other recent films. maybe all Safie films, maybe not. Marty Supreme uses Daniel Loin or one of Tricks Point never, as did good time with Robert Pattinson.

or no, maybe it was the Hacks and Cloak guy has been doing some stuff with scores. Daniel Loin has definitely been prolific in score creating lately. but like working actively with the director. Shaping it into something. it’s more like ambient textural. It’s not like Rd Berman where it could be a standalone pop song thing.

but it is an interesting counterpoint, like good stuff is getting made. but yeah, I, I would love for some film, bro, gender neutral term, to hit us in the inbox and be like, actually there is somebody doing this kind of thing. It’s probably my fear is that it’s something that we would both hate.

Some, like twee fucking Zoe de Chanel to, you know, person with an acoustic guitar commenting on what’s happening, like camp fiery vibe type. It would be my worst nightmare for somebody to be like. Something great is happening in film and it’s this and it’s just like people being sad with beautiful cinematography and somebody singing something fucking obnoxious.

Like, you know, a cover of a cover of a Phoebe bridger’s thing of Joan Baez, paper boy. Acoustic MP MP3 by Hannah. you got, you got me going. Full chat pile guy on this shit, man. Damnit.

Cliff: it’s agreed, but I’m glad that we’re talking about this ’cause like, it, it does help provide some sort of, contrast and relief to understand why we’re talking about already Berman this way. Like I would, so Yes. Agreed. Especially on, in the sense that I feel like most of the impactful songs made for movies lately have been like, oh look, they did smells like Teen Spirit, but sadder.

I’m like, yeah, okay, that’s good. It’s good, but like, but that did not happen because someone, someone was walking around all day going, I hear a noise in my brain that looks like to my brain, the thing that’s gonna be happening on screen while I’m doing it. And I’m not gonna stop until I find a way to make this noise and then make a song from it.

And then, okay, so my own counterpoint, I guess I do like Han Zimmer stuff and I do think Han Zimmer does.

Kyle: but I would put that in the big

Cliff: Yes. Okay. Fully

agreed.

Kyle: you know, tr tra

Cliff: of.

Kyle: comp.

Cliff: Yes. So it, it is the best of making sound effects that are impactful. Yeah dude, I go see Dune in fucking IMAX ’cause it sounds rad as hell. I get it. But like I don’t go listen to Hans Zimmer records and start bopping.

Kyle: Right.

Cliff: so that is the sort

Kyle: I listened to Han Zimmer to do TPS reports. Like a normal person.

Cliff: at this point, man, that’s better than listening to AI chill wave. So good for you

Kyle: Yeah, Yeah, that’s right. Or Taylor Swift Radio on Pandora.

Cliff: I would say then that, that was a fun little discussion. I would say then more specifically about some of these songs, so Countess Caper Mixes Jazz with the Italian Tarantella. So this is the thing that sounds like a

Kyle: Wait, that wasn’t the Curb Your enthusiasm theme.

Cliff: Wow. That’s.

Kyle: I’m sorry. Every time I hear tarantella up, Tarantella also sounds like, a Quentin Tarantino pasta To me, it’s just a strange word. Every tear Intella sounds like the curb theme or the music that a cinephile Larry David has chosen to be the musical backdrop of curb.

Cliff: Well, the reason that your comment made me laugh though, is because I was about to use the otherwise descriptive phrase of Bollywood spaghetti Western, which sort of like describes the things that are happening. But now you’ve put

curb there. Now you’ve put curbed and those things in the same container, and that’s just, that’s gonna impact me in a fun way.

But, but count as caper is a good example of, so those two things are happening kind of together. It is on its face, the thing that feels like, oh, we just grabbed some, like literally we like Western, Western movie soundtrack stuff, like Iio. And we’re just literally gonna integrate some of these noises that sound familiar, but this one’s cool.

’cause instead of mixing, it just makes a hard transition. It just starts with one and then it goes to the other. And like that, that sort of doesn’t happen again on this record. there’s a sort of fader that he’s got for the most part that’s happening throughout most of the rest of these, even when it’s happening as like background, soundtrack and all that.

But this one sort of shifts on purpose. That was interesting. It was kind of fun to start playing with it and try to understand then, okay, he’s borrowing these things and then that’s caught my attention about jazz. And there are several other moments of jazz throughout this soundtrack, but the one that caught me specifically was, baby let’s dance together.

Unironically. This would be a number one song today like,

Kyle: I said the same

Cliff: Yes.

Kyle: I said, you could cover this today, and it would be a smash.

Cliff: yes. Again, that is the one that made me think of like, and I really mean this in an endear way. I know we’ve been super sarcastic today, but like the coolest thing about TikTok is pulling up a video of like, here’s seven people in a room.

And they all rip and they’re smiling and they’re just like playing a thing, but like every single person is doing something worth paying attention to. And it just reminds you, like, how much is out

there and how, how, incredible people are. But this like baby lance dance together sounds like a lo-fi modern jazz hit made by a bunch of kids in their twenties. And it could easily go on a Jazz Dispensary record.

Kyle: For sure, for sure. Might, might be in the works for one. Who knows? There’s the, the backbeat is almost stacky to me. it’s very like bluesy kind of backbeat. And the bass licks are incredible. The flute is very swaggy. Rd Berman uses Western this in such cool ways, on baby LED stands together.

And then na day ta have very like western grooves and both are so swaggy. Like they could be samples for Clipse songs or something like that. but I did like that there was. Like sort of a seventies mod vibe to baby led dance together. Like it’s not disco e it’s a laid back backbeat that’s very like dude with sunglasses and a cigarette.

But then it’s got the like almost sixties Motown horns. little bit of like Ronnie Specter production, but not quite as loud. it’s spectacular. If there’s, I I totally agree that like there’s one artifact you pull from the whole record and it’s track seven of

10 back,

Cliff: a movie soundtrack.

Kyle: half of, yeah, back half of this record.

was that one of the ones that you were like, holy shit, in, in your notes? Yeah. Unreal.

Cliff: I, I know we talk about this a lot, but like, those are the sort of like flywheel moments on an album. You get excited about the thing and then you’re like, this was hiding from me and I didn’t notice it. There’s other shit that’s hiding from me now, and I’m, now I’m gonna go find it. and like, why is this

here?

Where did this just the constant ability to find a way to get interested in something happening musically. Just, I can never get over how, how rewarding it feels to have that skill. And it doesn’t go away. To me, it’s starting to feel like when I was in music school and you learn to sight read and I was talking to somebody about this recently, but it’s like, learning to sight read is pretty wild.

the idea is someone’s gonna hand you a piece of music you’ve never seen before, composed in one singular standard format across all instruments, and you’re just gonna go, yeah, okay. And then play it immediately. First time exactly as written on B, all of that. And when you first start doing that, you feel there, it’s like, there’s no way this is ever gonna happen.

It feels literally impossible in a way that makes you want to not be there anymore. Triggers every imposter syndrome that you possibly have buried all of it. it feels like it’s never gonna work and that there’s a trick that other people get that you don’t or something, right? And then you push and you push and you push and eventually it starts clicking and it’s still really frustrating.

And then one day it doesn’t feel frustrating anymore. It feels like a flywheel because you start, then you realize, wait a minute, I know how to do this. And the more that I do it on purpose in this really particular way, I can make myself better faster. And then that pays off in different ways. And then all of a sudden you can’t remember what it felt like to not be able to do this thing.

And not to give ourselves more importance than we need in this world or anything more importance than it needs, but like, this feels like a skill worth having. I keep not regretting having it. And I like this record again, reminded me of how, how this is like a muscle and it’s worth having for me because I was sincerely worried about talking about this record when we first came back to it again.

And especially after I saw all of those comments on 1,001 albums and I was like, shit, I don’t, all of a sudden I’m worried I’m

worried. I,

Kyle: my hobby

thing, by the way.

Cliff: exactly. and it just, it triggers the thing in you that’s like, I don’t deserve to be good at this, or I don’t know it, or there’s a secret or whatever.

And it’s like, I just, I want to keep reminding people of this this is such a cool thing. You can take albums and music and soundtracks from other people who you otherwise have nothing in common with or don’t know how to get along with, or don’t see what they enjoy about anything. And this skill will give you a way to get in a very cool door to everybody.

And being able to do it for movie soundtracks is extra cool because now this is everybody who cares a lot about movies but doesn’t think about music. Actually, we are doing the same thing, slightly inverted. I can show you this in two sentences and now we have somebody to talk about and that feels nice.

Kyle: And imagine at your next social gathering, being the person that’s like, Hey, has anyone seen 1970 eights shalamar? How’s everybody feel about Bollywood? And instantly, there’s probably like two people at a party I’m at. I’m at a party in reporting live from a party in Denver, Colorado, where I’ve just asked a bunch of white people how they feel about Bollywood films.

Cliff: I know that you’re making a joke. However, I was recently at a place with a bunch of people that you know and love who live here now, and we were all together

in a

Kyle: you were like, what’s up? Let’s talk about the joy of Rd Berman.

Cliff: of our good friends said to me, what’s the next episode? And I said, actually, and I gave a three sentence introduction. And buddy, there was a whole group conversation. Oh, for real? Why? What about it tell like, and yeah, it takes people who are interested in talking, but like, dude,

Kyle: You, you should be around those kind of people. If you’re, if you’re at a party full of not those kind of people, you need to fucking get in an Uber immediately. That’s just a life rule. You need, yes. And people, no, you don’t necessarily need to be friends with literal improv performers. ’cause that’s a whole other thing.

But you need people that observe the principle of adding to the conversation, not stopping it.

Cliff: yes. And it was a cool conversation because

I had no need to impress people with it. it was the like secret handshake thing that we’re always

talking about. It was the, no, if I tell these people about this, at least one of these people is gonna out of interest, go do this thing now that they wouldn’t have otherwise

done.

And now they’re gonna listen to Rd Berman when they might have never otherwise heard this person in their

whole life.

Kyle: That’s right. open a MUBI account to be able to watch shalamar the one place that’s currently available.

Cliff: Yeah,

Kyle: Yeah,

Cliff: it’s, man, it’s fun when you invent a

bit when we’re having this podcast and I’m like, I did, I did that though. We’ve been having that a lot lately. You’ve been texting

me stuff like, wouldn’t it be crazy if this happened? Like that literally happened to me yesterday.

Kyle: Just when I, maybe I just say it like that. ’cause that’s how weird everything in life is now. Wouldn’t it be crazy if this Yeah, it’s happening. like I’m, Rob Schneider in Surf Ninjas. Wouldn’t it be crazy if the house blew up? Still can’t surf either. are there other, any other highlight moments on the tracks for you?

Cliff: I would say no, not that stood out specifically in songs from here. What I’m interested to probably talk about next, as well as some of the recording technique, which was the next thing that really caught my attention. But, so for now, not as much about the songs, any for you.

Kyle: there are a couple other things that I, I just wanna spotlight and then I would love for you to talk about the recording techniques stuff because it is crazy. And I appreciate you bringing it to my attention. the two kind of other things that I, that really struck me. we’ve talked about, we’ve covered a lot of grounds, like, you’ve talked about like the hard cut. there’s really only like one or two hard cuts. The other one that I would point out is the romantic theme. The first half of it has almost like gothic overtones. It reminded me of the moodiness of a, foreign planet, like Fantastic Planet. And then there’s a hard cut into like a little musak thing.

So that’s an another little neat thing that I would look for. But the two things were, you know, we talked some about his interesting interpretations of Western and like, if you’re a person that’s only grown up on Western music like us, even some that’s been heavily Eastern influence, like we’ve talked about with Led Zeppelin and the Beatles and, stuff like that over the episodes.

A lot of good talk about that in the Ravi episode, if I recall correctly. but when I was listening to. Hum Wafa, the parentheses happy, the reprise version at the end, it reminded me of Roy Orbison. and there was something about the line, I wasn’t dishonest, but I wasn’t able to be honest. It just felt like the beautiful sadness of Roy Orbison, but like, it sounded like a Roy Orbison song to me.

And there’s no direct connection between Artie Berman and Roy Orbison as an influence or anything like that. But to your point about like the seven prolific musicians in a room on TikTok, just sight reading an idea, so to speak, that there’s like a, I can pull this sort of vibe from rock and roll or soul and evoke this feeling, that is in some of the Western music that I love.

I really like that and, And like do it in my own way. So, hum. Wafa, I think like, listen to the two versions and try to find some version of something that you really like in the romance of it. The other one though, inevitably there’s always a discussion about lyrics. Do, we love ’em?

Do we hate ’em? Do we need ’em? Are they there? words fail, music speaks all that, like regular refrain on this. I was so struck, not necessarily specifically by the lyrics on this, but there were some turns of phrase definitely that got me, but there were so many, they’d do like snippets, clips of music in the Poncho Unmixed that were like, holy shit. The translation was so. Devastatingly. Beautiful. Like I am a traveler without a home or destination. I just have to keep going on and on. Just keep going on. Sung in kind of a mournful, but kind of a happy way. then one right at the end when they were talking about his legacy after he had passed the boats.

Carrying souls in different directions will surely meet someday. That’s the shore that is destined for me, which reminded me of a lannigan song 100 days. That’s also about ships coming in. two people that never met or thought of each other, evoking an ache in the same, like using the same visuals.

Like that kind of stuff is so beautiful to me. but then. Reha, which is right after nata. So like my top three I would say on this record are baby, let’s dance together. The nata ’cause of that sick groove and very memorable.

Um, but then Aaina Wohi Rehta Hai, the vocals in that are very yearning and like, it’s so funny that that was just like a toss off motif with Brooks and Dudley. Men simply do not be yearning anymore. Once we said that. I have thought about that every fucking day since we recorded that episode.

My wife and I talk about it like the modern masculinity crisis. She’s watching heated rivalry right now, which sent us down other Jacob Tierney project rabbit holes. We started watching Shoresy and talked about how that, that’s like a romantic love letter to manhood and how to be a better man. And it’s so beautiful and like I kind of always just watched it before bad, not really in a state of mind to just appreciate it any more than a passing way or like, oh, they’re saying really funny stuff and there’s like good repetition, rhythm, but to the Charlie XCX, everything is beautiful point or everything is romantic.

the yearning vocals in there were like, okay, I gotta know what they’re talking about. A little. and the refraining that is, the mirror remains the same, but the faces change. And it’s talking about people deceiving each other or changing in love or, it not working out. But there is an ache in that.

and there’s so many instances I found in the teeny tiny bit of rough translations, shitty unreliable translations of his vast body of work. and I, you know, I won’t solely credit

him like on Shalamar specifically, he worked with Anand Bakshi, who was, awarded multiple highest possible honors for best lyricist during his career.

He wrote more than 6,000 film songs for more than 300 films. So every Brit as prolific as Artie Berman, he’s a, poet and

lyricist. and like, seemed Like he had sort of a, a mystic element to him as well. But it’s hard work to get. Into the lyrics as a person that’s only speaking English and you’re missing so much cultural context, time, period, context, all of that. And then there’s also the element of like, is it or is it not that deep? I think is, as we come to find, the evidence has mounted in favor of, even if somebody would say it’s not that deep about their own work, the fact that they strove to put it a certain way and they put it out in the world, you know, like, fuck Kurt Cobain’s, I’m just gonna say whatever pastiche of words thing, all of it meant something like, you can’t say that it didn’t mean something, or else you just would’ve made it instrumental, you know?

she loves you. Yeah, yeah, yeah. It’s still up for analysis. The same level of analysis as a. an acclaimed poet’s poem. Maybe not, but it still merits discussion. we can’t have a good, robust discussion about lyrics with this because we simply have a tall and wide language barrier here. But it has started an appreciation for me that I, I now want to go explore more and it was really kicked off by I know, Taha.

that’s the only other thing that I wanted to say is like a, sort of an, entry angle for me.

If none of the other stuff gets you

Cliff: Agreed. I will add my own curiosity ’cause I agree that his

little stanzas, he would

just drop throughout that documentary. Were

like,

damn, damn, a bar. Yeah. Yeah.

one of his, uh, a little bit of a preview here for something I wanna mention at the end, but his kind of swan song, so to speak, ended up

being after a very long story in his life.

in the, the nineties,

he sort of returned to fame and did 1942, a love story. And on that, you know, one of the most well-known songs he will ever, he ever did.

As of that soundtrack had just like, the lyrical structure is just three verses

of when I saw this one girl,

then I felt, and then he just does like this, like this, like this.

just one example. Okay. When I saw this one girl, then I felt like a blooming rose,

like a poet’s dream, like a brilliant ray of sunshine, like a deer in the forest, like a moonlit night, like a tender word, like a

candle burning in the temple. And then he does more of those for two more verses after that.

And just like I. Famously infamously and really annoyed by cheesy se, like overly simplistic lyrics or whatever. And this one just felt like someone has faith in the power of words. They’re like, no, no, I know how to say exactly what I’m gonna say. Here’s a simple structure. I’m gonna write a fucking poem. You’re welcome.

This is so good that the translation of it to English is gonna hit you over and over. And like respect, even if I don’t care necessarily, or it doesn’t influence the music I’m listening to in real time. Especially because it might not itself be in English. The knowledge of his capacity to use words.

And then, you know, also understanding, again, you know, his mother is, was a lyricist and he, how he worked with other lyricists and then vocalists and all that, created a real endearing sense of like, there is a lot of respect about the spoken word here in a way that I don’t always feel like comes through even with composers.

And, uh, I could not ignore that either.

Kyle: That’s a beautiful insight. I will reiterate my counterpoint that I know that I like lyrics in general better than you do, but I specifically like simple language as a person who helps people communicate professionally all the time. the number one challenge is just like, just do it simply.

Just say it the most direct way. If you were saying it to yourself, what would you say? and so I’m always gonna land on the side of, you know, is it going to be Keats or is it going to be. Piggy pops, no fun, my babe. No fun. what’s gonna land with a million people more easily? And in a time of a great terrifying literacy crisis, I am in favor of whatever type of words are going to draw people in.

And that’s always going to be the simplest thing. I’m not saying that’s what’s happening here, to your point, that it’s just the translation that that’s failing. But like I, I would go back to everything is romantic. I hope that somebody who loves Rd Berman in a far away part of the world comes across this and like, man, do I need to listen to Charlie XCX Now?

Was Rd Berman brat? That’s a sentence that is not happening on any other podcast guaranteed. but the first. Lines on that song are, bad tattoos on leather, tan skin, Jesus Christ on a plastic sign, fall in love again and again. And you’re like, fucking right. Everything’s romantic. That’s it. That’s the thought. That’s the tweet.

Cliff: Incredible connections happening here on Tune Dig. So let’s talk about then.

Kyle: What, what was happening in the studio?

Cliff: I definitely want to talk about the recording. Of this soundtrack. We don’t have to go into the depth that we’ve gone

into about other facets, but it is another pretty killer example

of the rewards

you

get by digging into Artie Berman and his approach, and

especially then specifically what is happening on this soundtrack.

And one of the legitimate reasons why this one specifically is very cool as an entry point into Artie Berman. So this

came out in 1978, so one of our favorite

overall themes on this podcast

is reminding people of phenomenons, such as the loudness

war or the invention of multi-track recording and dubbing, and how all those things

like literally will change music and how they had tremendous impact.

But, you know, if you weren’t there in the moment, you may not have noticed the

shift. so similarly, right about this time, the Shalamar soundtrack

is being recorded in stereo. At a time where the transition to stereo is still more or less happening to the degree that the studio that’s being used is not capable of doing a stereo recording.

And so what this means is that, if what I’m about to say doesn’t immediately sort of evoke a literal thing, this is probably worth a Google. or if you need to ask someone else or a chat or something, fucking fine. But like this is worth getting a little

Kyle: Phone a,

Cliff: a,

Kyle: don’t

you GBT.

Cliff: As long as a friend is telling

you about this, I really don’t care at this point. But, so in order to produce a stereo recording in a

studio that’s not set up for stereo

recording, what is effectively then being done are two recordings are

in a normal setting, you would be recording two

things one in a left channel, and one in a right

channel.

And then you’d probably put those together in

post-production because that’s what a reasonable person would do. But that’s not what fucking Artie Berman did.

’cause he rips, he said, let’s record this, let’s

make it in stereo live. So he

recorded. And I’m sure he got help

from other people, right? But like,

clearly this was part of the intent, or at least what they all decided to kind of do together.

So

they are in real

time recording two separate

channels, so left And

right. And so

first two rhythm sections were

used physically separated to capture the stereo effect. Again, live. You could have just recorded this separately and then put ’em together, but you’re gonna miss a bunch of the shit that ended up cool from this recording because it happened this

way. So two rhythm sections. One

is placed in the right channel with Franco in one channel and then v Desa and

another channel doing another rhythm section. Then for the bass guitar

throwback to anywhere between five and,

50 years. headphone splitter effectively was used a y connector, if you want to call it the cool version, but like a headphone

splitter was used to split the out output from the

bassist into two separate outputs so that they could be recording

simultaneously. so One channel going to the amplifier on the left side and then another amplifier on the right. And then they recollect that sound in the pseudo center of the recording. So again, all these are all things you could otherwise do in a more boneheaded way at this point if you wanna do a little bit more work.

But they did it on hard mode, which meant that everything got captured and some more kind of creative things could happen. So one, apparently there was one microphone that could record stereo even though the studio wasn’t set up for it. So the string sections was recorded with that microphone, which will create a slight, a very nuanced difference in how any of that stuff’s being heard in this composition so far.

And then on top of that, there

are moments in here, like one specific anecdote. So a boo

who was playing the french horn, choreographically was asked to walk from one place in the studio to another during the recording of the song so that the horn could be heard in

different

places. And so it’s like, okay, so already we’re

recording in separate channels.

We’re using headphones, splitters, we’re moving around French horn players we’re doubling and

layering things. And on top of that, there was an additional layer of only recording

some things on the left and only recording some things on the right. This happened live and Artie Berman choreographed literally switching left and right live during the recording to only capture one side or the other.

And like all

of this happened while the thing was being

recorded, not as little pieces that then got composed

and post-production their

way into an interesting thing. They did this whole thing hard.

the, respect I have for people who do shit like this

is unlimited, this is the most endearing thing I could have possibly heard until, and unless I hear that these are bad people, they are capital G, good people to me.

’cause

this is this is how you do

shit.

just digging into that again, like, that was another layer of what I was mentioning earlier where it’s like, I can lean in to the care

in this

music. every moment was

earned on purpose thoughtfully from composers and instrumentalists and

vocalists who care about the way that this sounded.

And were excited to work on this and like

did

the hardship to make it work and to conjure it, from their brains even before the technology made it easy.

Kyle: The other anecdote that I remember reading related that’s macro that speaks to the level of care. The micro thing for me was for Mera pr Shalamar, Asha Bole singing the vocals. one of the writings talked about how it. Used a far away echo effect and a cascading violin motif designed to sound like waves breaking in succession. So evoking nature of the world. but just thinking like, technologically, how are we going to do that in a, generous air quotes, call it pop song, a vocal song. But to give it some of that textural, cinematic feel. I love that there’s details big and small. Do you remember the like one of the first ones, first anecdotes about a studio trick or a like, oh my god, that’s too far.

But I love it and I would do it the same way. like, I can’t believe I never thought of that. I would do it the same way. can you think of a studio story where you’re like, I didn’t even know That was possible, but I respect the mania.

Cliff: My

earliest exposure

to those ideas were

Les Paul

in Page. So the very

specifically the people who wanted

to push the

edges of what and how was impacted by the presence of

electricity in guitar

music at

all. And

so the

first Les

Paul, basically just. Conjuring the

ability to record

multiple tracks by forcing technology

to work in that way is itself like

really cool and impressive and always was.

And

then,

you know, especially growing up in the

age of like, you know, I’d read Guitar World

Magazine and

all that stuff and they love telling stories about Led Zeppelin and all their weird

recording

shit and like

learning that Jimmy Page. speaking of complicated human beings who may not be capital G, good, fine, but like in terms of

commitment to

perfection and pushing boundaries in

how music was recorded,

I

mean, he is nearly unparalleled and reading so many of their stories just

about

like, once you embrace this

perspective of like the limitations in

music recording are set by other people, and I don’t have to agree to them, you start doing things

like recording drums in a stairwell because post-production reverb doesn’t behave the way that

you want it to behave.